I am an intermediate programmer.

I have a pretty good grasp of the basics. I have made enough mistakes to have a good idea why they were mistakes. I am aware that there is a lot that I need to know more about. Crucially, I have some idea of what those things are, and I am actively and energetically working on improving.

It has taken a while for me to get to the point where I am confident enough to admit that I am only average in ability. I no longer feel the need to hold second-hand opinions that I don’t really understand. I’m not so afraid of being found out when I don’t know about something.

It hasn’t always been this way. You might not credit it, but I used to be something of a programming guru.

This erroneous evaluation of my own ability can best be attributed to the relatively isolated environment in which I developed my skills. Back in those days, even owning a computer was a little bit special; knowing how to use it even more so.

By my own estimation, I was a pretty knowledgeable and experienced programmer. By the time I was barely out of my teens, I’d written programs in C++, Pascal, C#, JavaScript and - my crowning glory - I had written a custom e-commerce platform in PHP from scratch (more on this later).

In reality, I was perhaps just a few cuts above that “friend’s son who is a whizz with websites!” I had had no interaction with any other programmers, so my only point of comparison was the people around me; people who either didn’t bother much with computers, or if they did they probably had five spammy toolbars clogging up their Internet Explorer window. People who might well use the phrase “my Internet is broken.”

Here is the story of how I fooled myself into thinking I was much better than I was.

The Genesis of My Genius

When I was about nine years old, a friend of mine had satellite TV at his house. At home, we were limited to the standard four UK terrestrial channels (these were the days before Channel Five - how did we manage?), and I hankered after the overwhelming choice of bad TV that I had just witnessed. All we needed was one of those satellite dishes - or ‘satellites' as we called them - and I too would be able to watch QVC or Eurosport whenever I wanted. Somehow dimly aware of my nascent gift, I set about to build my own satellite (dish)! My design involved a fully opened umbrella and a length of copper audio cable, one end attached to the metal shaft of the umbrella, the other stuffed into my TV’s aerial socket. Admittedly, my design had some flaws, and consequently failed to deliver the expected results. However, the point of this anecdote is simply to demonstrate the technical ambition that would mark my childhood and adolescence. Nobody else I knew had even thought about making a satellite.

A few years later, I became an early-adopter of the Internet when my dad got a 14.4k modem at his office. I recall spending one Saturday afternoon patiently waiting for the flaming Manga logo gif to load, each subsequent frame appearing every minute or so. I even built my own website using Netscape Composer. Not yet aware of the architecture of the Internet, I saved my html files locally and then wondered when they would show up online. This detail, however, did not detract from the fact that nobody else I knew had made their own website.

By the time I reached my early teens, I discovered the darker side of my talent. Armed with a copy of the Jolly Rogers Cookbook, a couple of friends and I set about to shake the technological (and moral) foundations on which mid-90s England stood. Phreaking (that’s cracking phone systems) was our forte. We got as far as using a handheld acoustic coupler to make free international calls from public phones to American girls we’d met on ICQ and setting up voicemail boxes on private branch exchanges. Schoolwork and skateboarding prevented us from taking our exploits much further. Had we not such distractions, we’d have no doubt been regularly making napalm, hacking government networks and killing men with our bare hands. Although we failed to fully explore the limits of our powers, the fact was nobody else but us owned an acoustic coupler.

Despite my numerous adventures and misadventures with various technologies thus far, something was still lacking. My ideas were always several steps beyond my physical abilities - as highlighted by the “satellite” episode. I needed a way to get the contents of my mind out into the world. I needed a direct interface between my imaginings and reality.

The Fuck Generator

The true turning point came when I was about fourteen years old. I bought a copy of PC Plus magazine which included a cover CD featuring a full version of Borland C++ Builder. I installed it and carefully followed the “hello world” tutorial which was helpfully included in the magazine.

This was it. A new world opened up before me. The restrictions imposed upon my imagination by the material world were gone. My creativity unshackled, the cathedrals in my mind would be made manifest! To what lofty end should I put this new-found tool? It was obvious. The Fuck Generator.

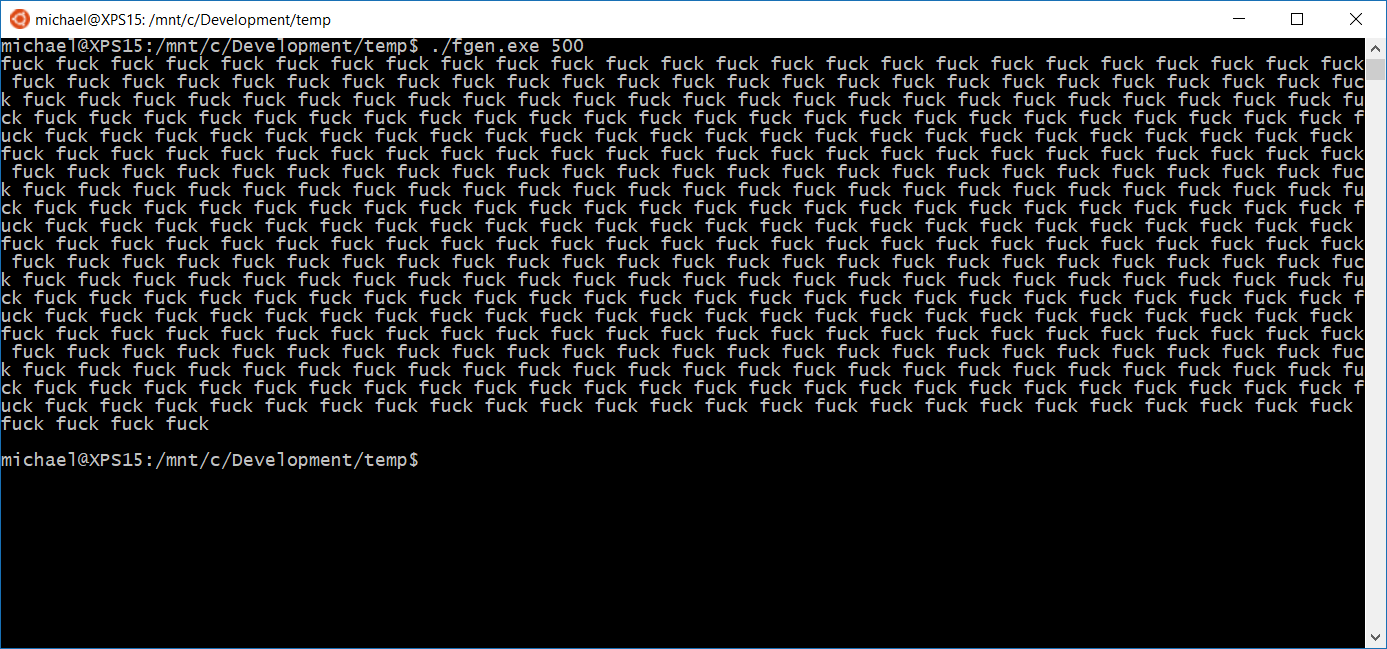

As simple as it was elegant, the Fuck Generator (fgen.exe) was a command-line program, and my first advance beyond “hello world”. Upon starting, it would prompt the user for a number. With this number n, it would then print out the string “fuck “, n times. Finally the user was given the option to repeat the exercise, or quit. Perhaps a little limited in use, I nevertheless was hooked on the power that I had tasted. It is a particular joy that any programmer will know well, to see the machine do your bidding, no matter how simple a task that may be. It works, and it works because you understand how to make it work. And it cannot do anything but work.

A short while later, another edition of PC Plus included a full version of Borland Delphi. With it, I upgraded the concept to include a Windows GUI and the ability to randomly generate colourful and sometimes surprising 4-part insults. While the other kids at school were passively playing PlayStation, I was engaged upon a far more meaningful and creative endeavour. I was generating fucks.

By this point, it was quite clear that I was destined for big things. It was time to show the world what I could really do.

Approximate output of fgen.exe

My Magnum Opus

In the late 90s, I created a website for a small but expanding mail-order retailer. At first, the site was just a few static pages - brochure-ware - complete with a navigation menu in a frameset and the obligatory visitor counter on the home page.

When we started getting more and more enquiries from the website, we decided to experiment with adding e-commerce functionality. We iterated over several off-the-shelf packages, whose quality ranged from utterly terrible to just terrible. My memory of the first version is predominated by fiddling about with cgi scripts and the bizarre use of <select> elements for almost all user interaction. A later version was a monstrosity of framesets and JavaScript - long before it was anywhere near advisable to base your app’s functionality on JavaScript. Another version was powered by a Microsoft Access database.

At length we came to the realisation that, if we wanted to have a genuinely okay-ish or even decent online shop, we’d need a custom solution. I considered my past success with fgen.exe and its sequel, not to mention a string of excellent websites I’d built by this time, case in point: my Manic Street Preachers guitar tab archive website was pretty authoritative, and a proud member of the “Manics Web Ring” (remember web rings?). I felt the time had come to really see what I was capable of. I’d build it myself. From scratch.

From scratch?! If open-source frameworks existed at that time, I didn’t know about them. No - I had my own plan. I bought a book on PHP and MySQL, and started to learn both technologies as I built the new website.

As luck would have it, the book featured as one of its central examples a very simple shopping cart application. All the parts were there - “category.php” would list all the products in a category; “product.php” would display the details of a product with a button to add it to the cart; and most importantly, “cart.php”, where the real magic would happen. This was clearly meant to be!

I followed the example studiously, faithfully implementing all the ingenious and no-doubt cutting-edge techniques - those handy “mysql_” functions for data access; string concatenation for building queries; separating functions into a “functions.php” file; including a “header.php” and a “footer.php” to maintain consistency site-wide; shunning the bulky overhead of the object-oriented approach (whatever that really meant) in favour of lightening-fast procedural code. My skills were increasing exponentially!

Like a one-man termite colony, I built towers and dug labyrinthine tunnels of code. The structure stretched both further skywards and deeper underground with each new feature that I added. And add features I did. Customer accounts, product ratings, order histories, reward points, voucher codes, special offers, logging, A/B testing, encryption of payment data, and on and on. A sprawling maze of interconnected dependencies, a galaxy of functions of all shapes and sizes, slowly spinning around a central, immovable hub: “cart.php”.

After about eight months of feverish work, it was finally ready.

Now, my knowing reader, you may be expecting me to detail how spectacularly, horribly wrong it all went once we flipped the switch on our new website. I am afraid I have to disappoint you.

It worked.

Worst Practices

Despite what I now refer to as my “worst practices” approach, the thing worked. Every bad tutorial, every anti-PHP blog post - it was all there. Spaghetti code? Check. Inconsistent naming of data and routines? Check. Presentation mixed - nay, fused - with business logic? Check. Magic numbers and global data galore? Check.

To me, the object-oriented approach was just a bunch of unnecessary overhead and boilerplate, and I had plenty of misinformation to back me up. I knew all about testing too - click through your feature a few times, seems good, upload to production! I was dimly aware of other (fancy, overly-complex) architectures but as far as I was concerned, mine was a perfectly sensible (and probably much faster) way of doing things.

The proof of my rightness in all these things was the fact that I had written, from scratch, with my bare hands and wits, a functioning and full-featured e-commerce website. Furthermore, one that performed well and was successful and expanding!

In my eyes, there was not much difference between me and the guys who wrote Amazon.com. Sure, Amazon was quite a bit bigger, but I saw no reason why my platform would not scale up without a problem - especially considering the blazingly fast procedural architecture I had used.

And so I had reached a plateau of skill as a programmer. That’s not to say I was disinterested in learning more - I just didn’t feel an urgency about doing so. After all, I had built something that worked and worked well. Surely anything beyond that was just a bonus, the cherry on top.

Back Down To Earth

This state of affairs prevailed, I’m sorry to say, for several years. I was only working on the site on a very part-time basis, spending the majority of my days working in a completely different field. Over the years of maintenance and the occasional adding of new features, I did develop an awareness that certain choices I had made were now proving to be bothersome. I noticed how long it sometimes took to find what I was looking for in the source files. I was perturbed by the number of minor bugs that would emerge in seemingly unrelated areas of the site each time I made a change.

My learning did not completely stagnate, but it did crawl along pretty slowly. For example, I came to learn that the mysql_ functions that I had used were now considered risky, to the degree that support would be dropped in future versions of PHP! For a long time, I countered any fears with the knowledge that my water-tight sanitization routines would more than make up for that. After all, I had tried various SQL-injection strings in pretty much every form input I could find, and it all seemed hunky-dory.

One day last year I got an urgent call - the website was down! Every request resulted in a 500 internal server error! After the engineer at the hosting company had got it up and running again and had conducted the post-mortem, it turned out we had been the victim of an exotic SQL injection attack, the like of which I had never seen before (in any of the several tutorials I’d read about SQL injection).

Alright, I thought, maybe it’s time to swap over to this new-fangled PDO thing I’ve been hearing about.

My Epiphany

When I sat down to re-write all the data-access functions, something profound occurred. I realised that this was going to be tough. And I realised why it was going to be tough.

It was going to be tough because these functions were scattered all over the place; because I had no real way of knowing if I was going to break something in some subtle way; because the code was inconsistent and I’d have to carefully study how each instance slightly differed from the last; because much of the code was tightly coupled with other parts which might also subtly break when I made changes. In short, it was going to be tough because of all the bad practices and lack of understanding that had informed the creation of this sprawling mess that only now revealed itself to me.

All the justifications, the defensive reasoning, the ignorance started to melt away. I had been wrong. I was not the sublimely gifted programmer I had suspected myself to be. I was a fake who had somehow gotten away with it for this long!

My folly had been thrown into sharp relief, and though this was a blow to my ego, it was also an incredibly valuable lesson. I learned first-hand - and painfully - why there is a right way and a wrong way to do things. It’s not just a matter of taste or fad. It’s not a matter of who has the cleverest arguments. The right way has real-world ramifications which will make your life (and the lives of others who touch your code) better. The wrong way leads to frustration and wasted time. I won’t try to address here the thorny issue of what exactly constitutes “the right way”. Suffice it to say it wasn’t what I had been doing.

The Real Sin

I did implement PDO. At the same time, I started using PHPUnit for the first time. Attempting to retro-fit that kind of code with unit tests is not something I would like to repeat.

Nowadays I make a conscious effort to push myself and learn more whenever I can. I am reading the books that programmers are supposed to have read. I’m following blogs. I’m listening to podcasts. I’m watching conference videos. I’m attending and even giving talks at local user groups. I’m working on side-projects to challenge myself to learn brand new technologies. I’m trying to learn the right way to do things.

For all you who are also engaged upon this task, there is an important factor in our favour. Being that programming is such an utterly abstract endeavour, the material-world limitations that characterize so many other fields simply do not apply. Here, the limiting factor is oneself.

I’ll close this story with some true words of wisdom. At the time I began drafting this blog post, I was just finishing the book Code Complete Second Edition by Steve McConnell. Towards the very end of the book, at the bottom of page 825, he writes something that perfectly articulates the exact sentiment I had in mind when writing this post. Perhaps it is telling that he was able communicate in two sentences what took me a couple of thousand words:

“It’s no sin to be a beginner or an intermediate. It’s no sin to be a competent programmer instead of a leader. The sin is in how long you remain a beginner or an intermediate after you know what you have to do to improve.”