Next week sees the close of my first year as an active participant on GitHub and in the open source community. I’d like to mark the occasion by collecting together a few thoughts on my experience thus far.

At the beginning of this year I wrote about my decidedly shaky start in the world of professional software development in the essay Confessions of an Intermediate Programmer. For those who have read the sorry tale, it’ll come as little surprise that it was only fairly recently that I started using any kind of version control system.

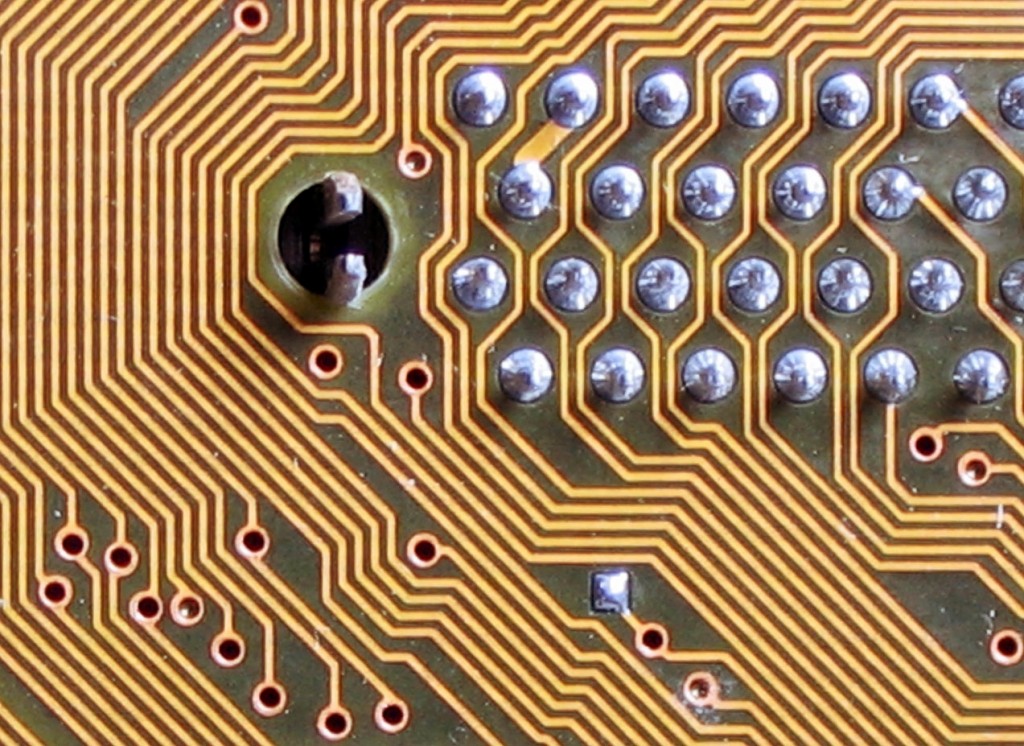

A couple of years ago a friend introduced me to Mercurial, and until recently I was what you could call a “light user” - my revision history graph was a boring vertical line as opposed to something cool resembling, perhaps, a London underground map or a close-up of a printed circuit board. Yes: source control for me was simply a glorified incremental backup.

At the end of last year I made a decision to actively improve my knowledge and skill as a programmer, and one thing on my to do list was to find out what this GitHub thing was all about.

Since then I think I’m getting the hang of it - I’ve published quite a few repos (some of which have actually proven useful to others), and this week I had my first pull request merged into a major project (a bugfix for Zurb Foundation)!

Social Coding

My biggest disadvantage as a programmer has been that I have always done it alone. I began by teaching myself, and then I worked for years without ever having another programmer look at what I had written. This, as you might imagine, resulted in some terrible habits and awfully ingenious “solutions”. One recent gem I uncovered during some refactoring involved a PHP function which dynamically assembled new PHP functions by string concatenation, and then stored the result in a database to be eval()ed later.

I still work alone most of the time, but I try to counteract the programming solitude by finding other ways to interact - attending user groups, reading the work and ideas of other developers and - increasingly - taking part in the open source community via GitHub. This last item has provided some of the most valuable interaction in terms of exposing me to new, better ways to do things.

An additional consequence of this is that I’ve finally started to get some use out of the distributed part of the distributed version control paradigm.

Open Source for Business and Pleasure

I’ve spent part of this year working on an AngularJS-based business application and I decided to open-source parts of it (with the client’s blessing) as an experiment to find out a) whether anyone else actually found them worthwhile and b) how the “bazaar” model of software development (open and seemingly disorganised; as opposed to the quiet, closed “cathedral building” approach) would work out for my projects.

a) It turned out that yes, quite a few people were running into the same problems as I, and wanted a ready-made solution. This is the pleasure part, since I - as I image do many of us - derive quite some pleasure from helping others out with something I have made.

b) So far, the bazaar model is working fantastically well for me. One module in particular - and my most popular by far - is a pagination solution for AngularJS. I am continually amazed by all the strange and creative ways people find to break the thing. And in doing so, they serve to expose yet another way it can be improved. I find this line I found on the Open Source Initiative’s website to be very true:

“The foundation of the business case for open-source is high reliability. Open-source software is peer-reviewed software; it is more reliable than closed, proprietary software. Mature open-source code is as bulletproof as software ever gets.”

Whereas the client may have paid for my time spent developing something that I then gave away for free, they in return get a much richer, more resilient product. Everybody wins!

Uh Oh, This Needs To Work Now

In writing and maintaining software that is used by people other than myself, I’ve also learned the importance of writing reliable, robust code and documenting it well. Anyone who has code that is in wide use will soon learn that a few hours spent making the docs clearer will save many times that in fielding requests for help later (or at the very least means you can simply provide a link to the docs instead of explaining it all again).

The experience has also brought home to me (once again) how automated testing is an utter necessity when it comes to fixing bugs or adding features whilst still being confident that I’m not breaking what already works well. Indeed, my most-used module has almost exactly double the number of lines of code dedicated to the unit tests than are used for the thing itself.

This is what happens when you have no regression testing

I’ve found that it can be easy to build something that works. To build something that works all the time, in any applicable context, is another thing entirely.

Issues With Issues

The act of creation brings with it responsibility for that which was created. My one-year-old son provides an inescapable reminder of this important truth. The same goes for my projects on GitHub. Since I mostly work on this stuff outside of my day-job, I cannot always address issues as soon as I’d like. Of course, I always know about the issue within a short time of it being created, thanks to GitHub’s friendly email alert service.

The open issue - especially the one that I have no clue yet how to solve - is somehow especially offensive to my mind’s desire for completion and perfection. Imagine having painted a portrait that looked almost perfect, and then someone points out the slightly weird left eye. From then on all you ever notice is that wonky eye.

The worst is when I read a new issue just before going to bed, and then can’t help but stay awake thinking about how to solve it.

To bring this point back to the children analogy: I sometimes find myself awake at hours that I would not normally choose, rocking my son back to sleep. Likewise, I sometimes find myself working a little extra in the evening, investigating that edge-case bug that someone uncovered. Both are relatively minor annoyances when compared to the overall value of the creative act.

I Am Human and I Need To Be Loved

As with the Facebook and Instagram “like” or the Twitter “favorite”, the GitHub Star is a way to express a unary opinion (“it is good”) of something offered to the world.

I have an uneasy feeling about these features generally. Of themselves, they offer a useful way of getting some simple feedback. Nobody likes the thought that nobody cares. However, I also think they can encourage a kind of unhealthy inversion whereby we begin to hang our own self-worth on what others think of what we do, rather than whether what we do is in accordance with our own values and convictions. That is not to say that we should not welcome feedback and helpful criticism, but an over-importance placed on likes, favourite or stars (or any other kind of fake Internet points) strips us of the power to decide our own worth and places it in the hands of others.

Since the Internet enables a sort of offhand, impersonal unkindness that doesn’t usually pass in real-life communication, such an inversion leaves people wide open to belittlement by others - both intentional and otherwise. I’ve even seen people get actually upset when their photo or status didn’t generate the expected number of likes on Facebook. This is more of a general point on Internet culture, but I’ve seen it play out to a lesser extent on GitHub from time to time, too.

In the context of GitHub, a programmer may get the idea that, because his or her offering has received fewer stars than other projects out there, it is somehow inferior. Maybe it is inferior. Or maybe it is so wildly forward-thinking that fewer people can appreciate it. Or maybe he or she is no good at promoting it. The point is, the star count should not be the only indication of worth.

That caveat aside, I do find the star feature useful overall, and I do use it as a way to signal appreciation for the work of others. As a feedback mechanism it is crude, but given the nature the GitHub social network, I’d also say that a star has more substance to it than a Facebook like.

And I’ll admit that I do like it when people star my projects. I am human, and I need to be loved, just like everybody else does.

Looking Forward

I’ve had a lot of fun with GitHub so far. I’ve already got some plans for new projects to kick off 2015, and of course I’ll keep fielding the issues on my existing repos.

This will be my last blog post for 2014, so happy New Year and here’s to a successful and productive 2015!