I’ve recently been listening to the excellent podcast series Revolutions by Mike Duncan. Right now we are in the thick of the French Revolution. It’s really riveting stuff, and offers some fascinating insights into the interplay of groups, ideology, virtue, violence and terror. If that list sounds familiar, perhaps you frequent Twitter or Reddit or some other online community.

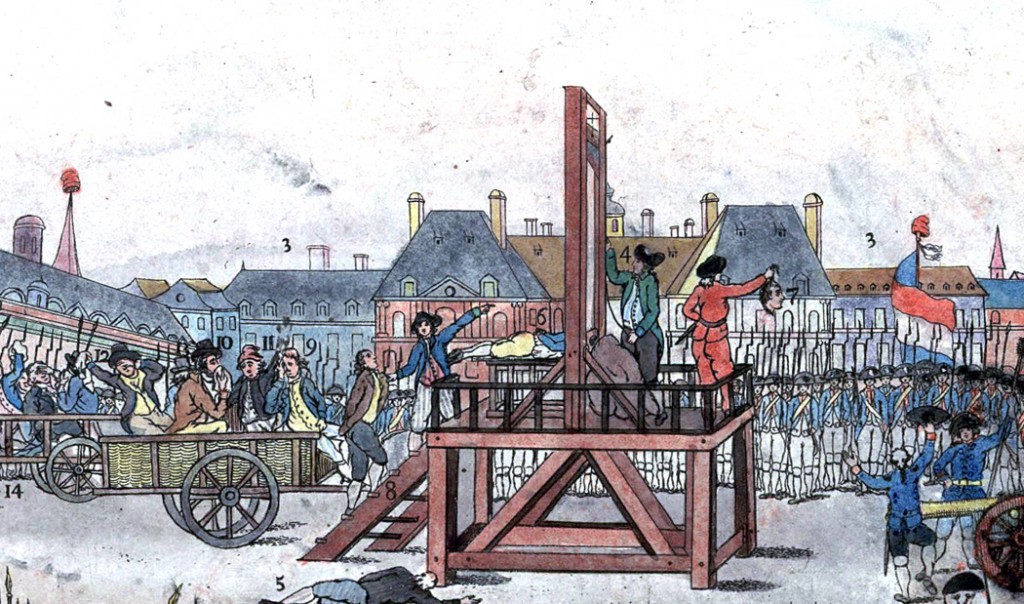

Detail from a painting of the execution of Robespierre

Ah, the Internet - the defining technology of the new Information Age. An amplifier of everything good, bad, and downright weird about humanity. From the comfort of our sofa, bed or even toilet (come on, admit it…), we can enjoy the spectacle of human interacting with human.

Amongst the many and varied aspects of online interaction, there is a certain pattern I have noticed which harks back to the tumultuous times of the French Revolution - a seemingly innate dynamic of groups which repeats throughout history and which finds expression again, two centuries later, on the Internet: ideals enforced by terror.

Literally Robespierre

Those familiar with Internet discussions will know that they readily devolve into comparisons to Adolf Hitler and/or Nazism - sometimes more than mere comparison, as in the epithet “literally Hitler”. This phenomenon is formalised in Godwin’s Law. I’d like to propose, however, that in many cases a comparison to French Revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre or perhaps Jean Paul Marat would be more fitting. I’m not expecting the practice to catch on but hey, if it does, I’ll happily lend my name to it.

The Scene

Paris, 1794: The guillotine is sated daily by a steady stream of counter-revolutionary conspirators. Maximilien Robespierre, now the effective dictator of France, is guiding the Revolution down an exceedingly narrow and dangerous path towards his Republic of Virtue - supposedly the embodiment of the ideals of the French Revolution: liberty, equality, fraternity.

With Robespierre at the helm of the near omnipotent Committee of Public Safety (which, contrary to the tame-sounding name, was not primarily interested in warning labels and slippery surfaces), France found itself under the de-facto dictatorship of a man who would publicly proclaim,

If virtue be the spring of a popular government in times of peace, the spring of that government during a revolution is virtue combined with terror: virtue, without which terror is destructive; terror, without which virtue is impotent. Terror is only justice prompt, severe and inflexible; it is then an emanation of virtue;

— Maximilien Robespierre, 1794

That is to say, “be virtuous or die”. It turned out that nobody except Robespierre himself really knew the precise definition of virtue in this case; thus many people would have to die. This period is known today as the Reign of Terror.

Four years prior to the official sanction of terror as a tool of the state, the nascent Revolution had produced The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, a document exemplifying Enlightenment thought which would leave a lasting imprint on the development of democracy in Europe and around the world. The second article of the declaration states:

The goal of any political association is the conservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, safety and resistance against oppression.

— Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, article 2, 1789

Long story short (and for the long story, I urge you to check out the podcast): what started as a bold struggle for liberty in the face of age-old aristocratic power ended up devouring itself in an orgy of violence, paranoia and injustice. The Revolution at length sought to bring freedom of speech to all by arresting and executing those who spoke against it. The radical had become the new orthodox; justice and humanity were replaced with brutal ideology.

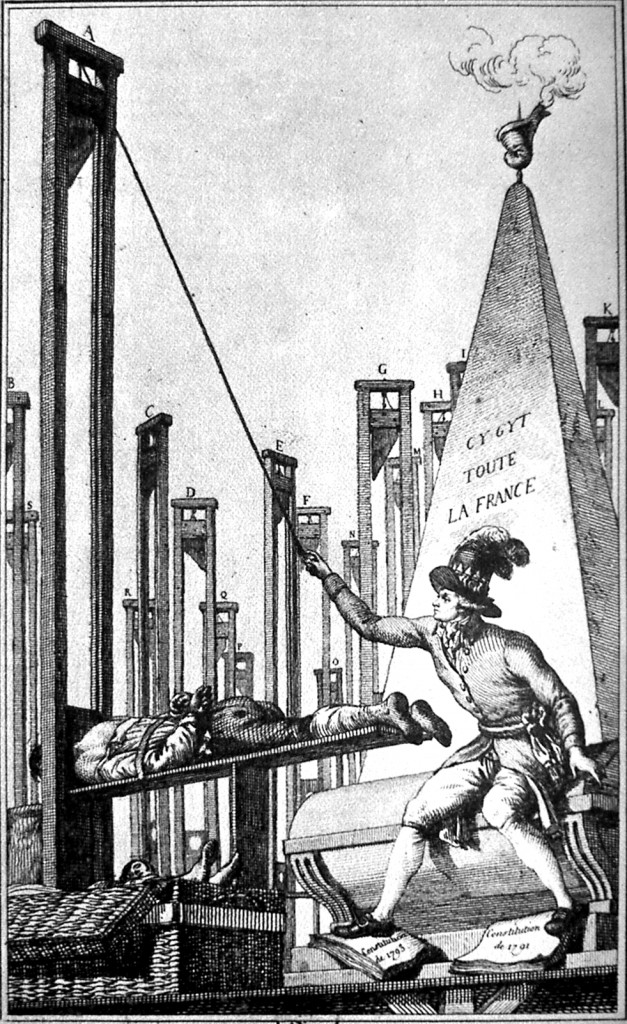

Robespierre guillotines the executioner, having guillotined everyone else in France

Enlightenment 1.5.0

The principles and freedoms of the Enlightenment - which dramatically culminated in the French Revolution - have latterly been extended by the advent of the Internet. While perhaps not quite a “Second Enlightenment”, several new features have been added (all backward-compatible), hence 1.5.0.

Admittedly, its main uses may actually be porn and spam, but nevertheless the Internet does offer an egalitarian platform for discussion wherein any and all ideas are open to debate and criticism.

Where the French Revolution granted fair representation to the Third Estate (the common people), the Internet has given a voice and a common platform to previously marginalized subjects and alienated groups.

These are the virtues promised by the Internet: diversity of thought, compassion, tolerance, a shared enlightenment.

Like the Revolutionary ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity, these are agreeable concepts that most people can get behind. And like those Revolutionary virtues, they can also be perverted and pressed into a tool of terror by bullying ideologues.

Tolerance

One central virtue which sprang forth from the Enlightenment and the Revolution (at least on paper) was the idea of tolerance. Let us first define what it means to tolerate:

tol·er·ate: allow the existence, occurrence, or practice of (something that one does not necessarily like or agree with) without interference.

Celebrated French thinker Voltaire, a forerunner of the Revolution, is widely quoted thus:

I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.

— not Voltaire

"Don't quote me on that" - Voltaire

That’s actually a misattribution (the Internet is a pro at those), so here’s something that Voltaire did actually say:

Tolerance has never brought civil war; intolerance has covered the earth with carnage.

— actually Voltaire, full text here

This attitude was enshrined in the mission statement of the Revolution: again, from the Declaration of the Rights of Man:

No-one shall be interfered with for his opinions, even religious ones, provided that their practice doesn’t disturb public order as established by the law.

— Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, article 10, 1789

All good stuff, I’m sure you can agree. But after reading such sound, compassionate words of wisdom, you might be left wondering, “what the bloody hell went wrong?”. While that’s probably a question for a proper historian, I will at least attempt a partial explanation; one which I believe also goes some way to explaining the parallel fate being suffered by our modern Enlightenment 1.5.0 virtues.

Group Polarization

Group Polarization is a term used to describe the phenomenon whereby people placed in group situations tend to form more extreme opinions than they would on their own. Read the full Wikipedia entry - it’s fascinating. It offers a compelling explanation of the kind of radicalization and extremism that turned the French Revolution into the Reign of Terror. It is probably at play in any case of extremism you might care to mention.

The Wikipedia article states that the phenomenon “has shown that after participating in a discussion group, members tend to advocate more extreme positions and call for riskier courses of action than individuals who did not participate in any such discussion.” And moreover, “as long as the group of individuals begins with the same fundamental opinion on the topic and a consistent dialogue is kept going, group polarization can be observed.” (my emphasis added)

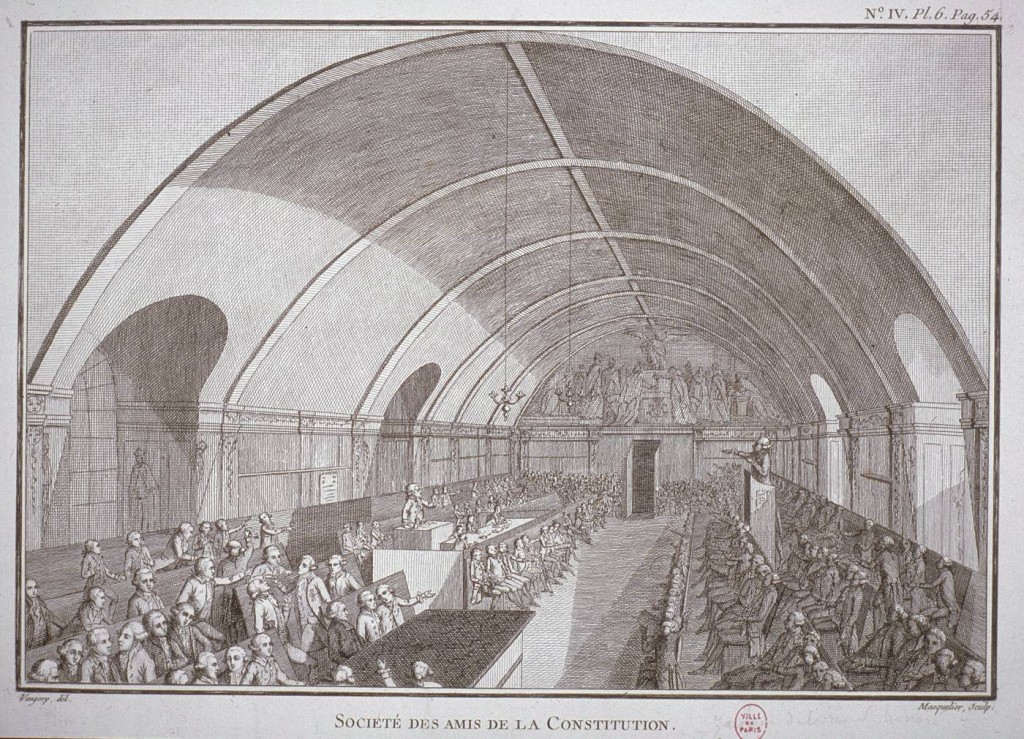

Revolutionary circle jerk: A meeting of the Jacobin Club, 1790.

The French Revolutionaries were really into discussion groups. The Jacobin Club, the most influential of these groups, became progressively more radical and culminated with the rise of Robespierre and the institution of the Terror. Over the course of a few years the group’s republican orthodoxy shifted so far to the left that many original members - all republican radicals at the time - eventually came to be viewed as too conservative and thus as enemies of the revolution.

We also love our discussion groups. Chat rooms, IRC, Reddit, Twitter, and probably a whole bunch of things I’m not hip enough to know about. With the global and ubiquitous nature of the Internet, a consistent dialogue on a polarizing topic is not only feasible, it is the norm. When group polarization takes hold, we might call it an echo chamber or a circle jerk, but it is essentially the same thing.

In the interests of being nonpartisan, I have decided to refrain from citing specific examples, but they are not hard to find. Instead, let’s take a hypothetical online community who are united by a support for cause X. We’ll assume that cause X is something generally agreeable. As the discussion of X develops over time, polarization starts to kick in. The distinction between Xers and non-Xers grows more and more pronounced. An orthodoxy develops which admits of less and less deviation. Outsiders who stumble into the discussion are unable to navigate the accumulated culture and orthodoxy, are thus can be dismissed as a non-Xer.

From time to time a Robespierre or a Marat will arise - an incorruptible zealot of X. When this occurs, the orthodoxy will shift further to the extreme. Non-Xers start to look a whole lot like anti-Xers. At last, the group may start to look outside of itself to find and correct offences against X. Of course, by this time, with such an extreme and narrow concept of what really constitutes X, anti-Xers will be found everywhere. Previously disinterested parties will pick up on this obnoxious behaviour and decide that, hey! X and Xers need to be stopped! Cue the next online war.

The Enraged Ones

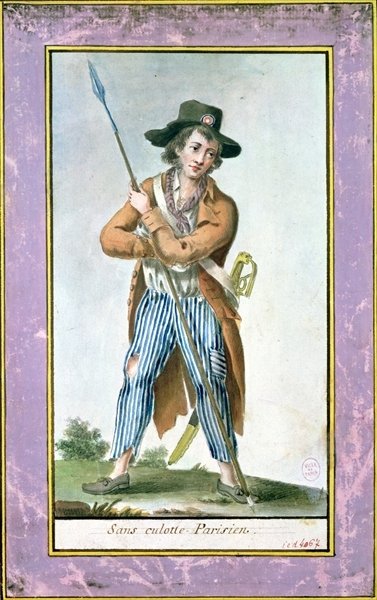

One of the constant forces of the French Revolution was that of the common people of Paris - the sans culottes, or roughly “those without fancy pants”. The sans culottes were rightly angry at the years of injustice and abuse at the hands of the old order, and played a decisive role throughout much of the Revolution. Their righteous anger made them easily-mobilized mob which could be pressed into violent action by a skilful demagogue.

A Parisian sans culotte. Yep - definitely not fancy.

One notable group of sans culottes leaders were known as Les Enragés, or The Enraged Ones, on account of them being so badly pissed off. The Enragés were, for a time, a powerful driving force in the radicalization of the Revolution. Through the rhetoric of violence and injustice, the Enragés and other radical leaders were able to keep the sans culottes in a state described by historian G. A. Williams as “permanent anticipation of betrayal and treachery”.

The result of all this was an atmosphere of fear and suspicion where the threat of denunciation was ever-present and had dire consequences. On the narrow road to Republican Virtue, a denunciation was not hard to come by. The mere accusation of royalist sympathies was enough to earn the accused jail time, if not an appointment with Mme. La Guillotine.

The modern-day Enraged Ones are likewise a force to be reckoned with. Much has been written about the Twitter “outrage machine”, wherein the mob gleefully administer the online version of a bloody good kicking to those who stray too far from virtue. Indeed, this is the Internet’s answer to Robespierre’s “prompt, severe and inflexible” justice. Reddit boasts a famously eager mob which can get acutely whipped up in the service of a noble cause. As I write this, there is a huge story blowing up about the latest high-profile victim of a Reddit campaign. Another glorious victory for X!

Such behaviour is not limited to one or another side in the many raging online wars. All sides play host to their own Robespierres and their own Marats. And while nobody is actually getting their heads chopped off (yet), the online mob can and does wreak havoc on the lives of those on the receiving end. The atmosphere of “permanent anticipation of betrayal and treachery” persists in the online Republic of Virtue.

Denunciation and Difference

A common thread of all repressive regimes is the constant fear of denunciation. The Inquisition, the witch hunts, McCarthyism, and on and on. During the French Revolution, the typical charge would be that of being a “closet royalist”. At the height of the Reign of Terror, the mere suggestion would be sufficient to get the accused locked up or even executed.

Latterly it seems that online denunciation has become something of a sport. The prize is known variously as karma, retweets, or generally just the approval of the other members of the Jacobin Club. Instead of jailings and beheadings, we get harassment and sackings.

My own theory is this: during the times of the Revolution (and in all such tumultuous upheavals), the usual societal mores are suspended. The veneer of civilization is removed and the moderating influences of a sophisticated culture are replaced by more primal instincts. Under such pressure, sober humanity yields to reckless inhumanity. Group polarization flourishes.

The Internet, by its relatively anonymous, impersonal nature, is already half way towards that inhuman state, even at the best of times. Cruelty comes more easily when we are not required to confront the human at the other end. Thus it does not take much to tip whole groups over the edge. Moreover, we tend to divide ourselves according to existing interests and values; again, conditions conducive to group polarization.

The keynote of cruelty is difference. During the Reign of Terror, suspected royalists and counter-revolutionaries were no longer considered countrymen, thus violence against them needed no further justification. Crimes against humanity generally occur where one group of people are considered so different as to no longer be truly human. Aristocrats, intellectuals, kulaks, slaves: history abounds with examples of groups considered so different as to justify oppression and inhuman treatment.

The end result of group polarization is a position so far from the middle ground, so different from the rest, that it at last becomes impossible to identify at all with outsiders.

"The Aristocratic Hydra" - and you know what we do to hydras, right?

Conclusion

So if there is any point to this essay - my “Jerry’s final thought” - it is the following: beware those who seek to define others solely by their differences. When you address someone, address them as a fellow human first. No matter the argument, we each have vastly more in common with any other human being than we could possibly have differences.

Furthermore, being extreme and radical is usually only a good idea in the context of sports like extreme ironing. As dull as it might sound, the measured middle is often closer to the truth than either extreme.

None of this is to say that we should remain silent and passive to wrongs that we see online. This too would be a failure of Enlightenment 1.5.0. Rather, we should strive to challenge ideas with rational discourse and without losing a sense of common humanity.

Here’s a thought experiment: Next time you feel like lashing out at somebody online (and we must all feel that way from time to time), try to imagine that it was your mother or your best friend who just wrote that. Would you respond any differently?

The question remains: with our new-found instant access to the whole gamut of the mankind’s ideas, beliefs and attitudes, are we heading towards Enlightenment 2.0, or a new Republic of Virtue? Will we collectively work to promote understanding or will we, to paraphrase Voltaire, continue to “cover the Internet with carnage?”

From the French Revolution Digital Archive

Postscript: Thanks to Ali Sharif (@sharifsbeat) for feedback and suggestions, and to Mike Duncan for making the study of history so accessible.